Any drug with the potential to cause toxic reactions to structures of

the inner ear, including the cochlea, vestibule, semicircular canals,

and otoliths, is considered ototoxic. Drug-induced damage to these

structures of the auditory and balance system can result in hearing

loss, tinnitus, and dysequilibrium or dizziness.

The propensity of specific classes of drugs to cause ototoxicity has

been well established, and over 100 classes of drugs have been

associated with ototoxicity.

Ototoxicity came to the forefront of clinical attention with the discovery of streptomycin in 1944. Streptomycin was used successfully in the treatment of tuberculosis; however, a substantial number of treated patients were found to develop irreversible cochlear and vestibular dysfunction.[1] These findings, coupled with ototoxicity associated with later development of other aminoglycosides, led to a great deal of clinical and basic scientific research into the etiology and mechanisms of ototoxicity. Today, many well-known pharmacologic agents have been shown to have toxic effects to the cochleovestibular system. The list includes aminoglycosides and other antibiotics, platinum-based antineoplastic agents, salicylates, quinine, and loop diuretics.

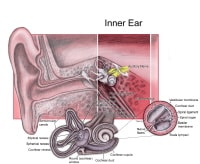

An image depicting inner ear anatomy can be seen below.

Inner ear anatomy. Ototoxicity is typically associated with bilateral high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss

and tinnitus. Hearing loss can be temporary but is usually irreversible

with most agents. Generally, antibiotic-induced ototoxicity is

bilaterally symmetrical, but it can be asymmetrical. The usual time of

onset is often unpredictable, and marked hearing loss can occur even

after a single dose. Additionally, hearing loss may not manifest until

several weeks or months after completion of antibiotic or antineoplastic

therapy.

Inner ear anatomy. Ototoxicity is typically associated with bilateral high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss

and tinnitus. Hearing loss can be temporary but is usually irreversible

with most agents. Generally, antibiotic-induced ototoxicity is

bilaterally symmetrical, but it can be asymmetrical. The usual time of

onset is often unpredictable, and marked hearing loss can occur even

after a single dose. Additionally, hearing loss may not manifest until

several weeks or months after completion of antibiotic or antineoplastic

therapy.

Vestibular injury is also a notable adverse effect of aminoglycoside antibiotics and may appear early on with positional nystagmus. If severe, vestibular toxicity can lead to dysequilibrium and oscillopsia.

Permanent hearing loss or balance disorders caused by ototoxic drugs may have serious communication, educational, and social consequences. Therefore, the benefits of ototoxic drugs must be weighed against the potential risks, and alternative medications should be considered when appropriate. Management emphasis is on prevention, as most hearing loss is irreversible. No therapy is currently available to reverse ototoxic damage; however, basic scientists and clinicians are continually seeking to find new methods to minimize ototoxic injury while retaining the therapeutic efficacy of these agents. For severe hearing loss, amplification may be the only treatment option

Ototoxicity came to the forefront of clinical attention with the discovery of streptomycin in 1944. Streptomycin was used successfully in the treatment of tuberculosis; however, a substantial number of treated patients were found to develop irreversible cochlear and vestibular dysfunction.[1] These findings, coupled with ototoxicity associated with later development of other aminoglycosides, led to a great deal of clinical and basic scientific research into the etiology and mechanisms of ototoxicity. Today, many well-known pharmacologic agents have been shown to have toxic effects to the cochleovestibular system. The list includes aminoglycosides and other antibiotics, platinum-based antineoplastic agents, salicylates, quinine, and loop diuretics.

An image depicting inner ear anatomy can be seen below.

Inner ear anatomy. Ototoxicity is typically associated with bilateral high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss

and tinnitus. Hearing loss can be temporary but is usually irreversible

with most agents. Generally, antibiotic-induced ototoxicity is

bilaterally symmetrical, but it can be asymmetrical. The usual time of

onset is often unpredictable, and marked hearing loss can occur even

after a single dose. Additionally, hearing loss may not manifest until

several weeks or months after completion of antibiotic or antineoplastic

therapy.

Inner ear anatomy. Ototoxicity is typically associated with bilateral high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss

and tinnitus. Hearing loss can be temporary but is usually irreversible

with most agents. Generally, antibiotic-induced ototoxicity is

bilaterally symmetrical, but it can be asymmetrical. The usual time of

onset is often unpredictable, and marked hearing loss can occur even

after a single dose. Additionally, hearing loss may not manifest until

several weeks or months after completion of antibiotic or antineoplastic

therapy. Vestibular injury is also a notable adverse effect of aminoglycoside antibiotics and may appear early on with positional nystagmus. If severe, vestibular toxicity can lead to dysequilibrium and oscillopsia.

Permanent hearing loss or balance disorders caused by ototoxic drugs may have serious communication, educational, and social consequences. Therefore, the benefits of ototoxic drugs must be weighed against the potential risks, and alternative medications should be considered when appropriate. Management emphasis is on prevention, as most hearing loss is irreversible. No therapy is currently available to reverse ototoxic damage; however, basic scientists and clinicians are continually seeking to find new methods to minimize ototoxic injury while retaining the therapeutic efficacy of these agents. For severe hearing loss, amplification may be the only treatment option

No comments:

Post a Comment